Martin Luther King., Jr., Workers' Rights, and Domestic Labor, An Original Post by Emily K. Abel and Margaret K. Nelson, Coauthors of LIMITED CHOICES

Martin Luther King., Jr., Workers' Rights, and Domestic Labor, An Original Post by Emily K. Abel and Margaret K. Nelson, Coauthors of LIMITED CHOICES

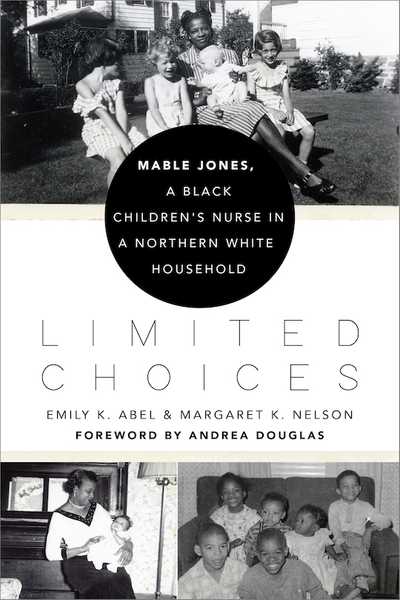

We are pleased to offer this original blog post in honor of MLK Day by Emily K. Abel and Margaret K. Nelson, coauthors of LIMITED CHOICES: Mable Jones, a Black Children's Nurse in a Northern White Household, with a foreword by Andrea Douglas.

*************

In a speech before the Teamsters and Allied Trade Councils, New York City, in May 1967, Martin Luther King, Jr., said, “Today Negroes want above all else to abolish poverty in their lives, and in the lives of the white poor. This is the heart of their program. To end humiliation was a start, but to end poverty is a bigger task. It is natural for Negroes to turn to the Labor movement because it was the first and pioneer anti-poverty program.”

Because Martin Luther King, Jr., advocated for unions and workers’ rights, his birthday is a fitting opportunity to examine domestic labor, the occupation of most African American women in the early twentieth century. Our book, Limited Choices: Mable Jones, a Black Children’s Nurse in a Northern White Household, introduces a woman who was a household worker for more than seventy years. Mable Jones was sixteen in 1925, when she first arrived in Charlottesville, Virginia, from a rural area with her widowed mother and four siblings. Three years earlier, she had begun her long career in domestic work. “I used to wash dishes for somebody in a home and go to school,” she told an interviewer. Mable Jones left school after eighth grade because, she said, “I wanted to get a better job and help my mother. She raised five children.” In Charlottesville, Mable Jones’s mother hoped to find better schools for her younger children and higher paid jobs for her daughters and herself. The tightening grip of Jim Crow, however, prevented her from fully attaining either goal. In the end, Mable Jones remained a household worker until she was 85, long after many African American women had found other occupations.

A quarter century after Mable Jones’s death, it is still all too easy to find evidence of systemic injustice in the kind of employment she held. Today, most of the 2.5 million private household workers in the United States are immigrant women from Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America. In significant ways, however, domestic service remains remarkably similar to the occupation Mable Jones entered a century ago. Household workers are now entitled to receive Social Security, but fewer than 9 percent of employers pay into the system. In addition, domestic workers still lack basic job protections. Three major pieces of legislation -- the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1967, and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1971 – do not cover those in jobs with single employees. The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 explicitly excludes domestic workers.

With few legal safeguards, private household workers remain vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. Nearly a fourth are paid beneath the state minimum wage; more than two thirds receive less than $14 an hour. As many as sixty percent spend more than half of their wages on housing. A third of them reported working long hours without a break in the past year; another third reported having been injured or exposed to toxic chemicals on the job. Fearful of deportation, undocumented workers are especially wary of complaining about employment conditions.

And household service work continues to tear families apart. When Mable Jones lived in her employers’ homes, sometimes several states away from Virginia, she left her children in the care of her mother. Today, large numbers of workers still leave children behind, in the care of grandparents and other kin. Although some take advantage of modern communication methods like Skype and Zoom, the periods and distances of separation are far greater than they were for Mable and her sons. Undocumented workers face overwhelming obstacles when they try to travel home or bring their children to the United States.

As an isolated and largely invisible labor force, domestic workers are notoriously difficult to organize. New groups of activists, however, have taken up the challenge. Founded in 2007, the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA) is a network of advocacy organizations including four local chapters and 63 affiliate groups. The director is Ai-jen Poo, the child of Taiwanese immigrant parents and a recipient of a MacArthur “genius grant.” Poo views herself as building on the successes of her predecessors, most notably Dorothy Lee Bolden, who helped workers in Atlanta win inclusion in labor laws in the 1960s and 1970s. In addition to launching a broad-based political campaign, the NDWA sponsored the first national survey of household workers, drafted a Domestic Workers Bill of Rights (including overtime pay, one day off each week, and protection under state human rights laws), and then lobbied to secure its passage in Congress and various state legislatures. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the group raised money to provide emergency assistance to domestic workers to enable them to stay home. Poo acknowledges that bringing household workers together to fight for better employment conditions might be “a never-ending project.”

Although this has arrived too late for Mable Jones and the many women of her generation, the emergence of a powerful new movement for workers’ rights offers considerable hope. Its current initiatives will help to make King's dream a reality.

QuickLinks

Find a BookFor Our AuthorsRights and PermissionsRotunda Digital ImprintSupport UVA PressCareer OpportunitiesWalker Cowen Memorial PrizePrivacy PolicyContact Us

- P.O. Box 400318 (Postal)

- Charlottesville, VA 22904-4318

- 210 Sprigg Lane (Courier)

- Charlottesville, VA 22903-2417

- 434 924-3468 (main)

- 1-800-831-3406 (toll-free)

- 434 982-2655 (fax)

the future

of publishing

Affiliates